Is poor posture affecting your breathing?

August 13thWe inhale. We exhale. O2 in. CO2 out. It seems simple enough; however, the majority of us are quite inefficient when it comes to how we breathe. It should come as no surprise that our increasingly sedentary lifestyle and slouched spinal postures would impact our ability to breathe well, but to what extent?

The average Australian spends nearly 10 hours a day sitting. A sedentary lifestyle has been defined in research by less than 5,000 steps a day or sitting for a minimum of 6 hours a day. Now if you factor in a daily commute, sitting down for meals, watching TV, etc. we can easily hit 6 hours of sitting before even adding on the number of hours we manage to sit at work or university. As humans, our bodies are designed to be in constant motion and when we don’t move, there is an application error in our physiology which causes us to function inefficiently. We live in a modern world that promotes this type of dysfunctional lifestyle, and it comes with a hefty price tag.

Anxiety. Depression. Obesity. Cardiovascular disease. Coronary heart disease. Diabetes. Cancers. Musculoskeletal injuries. The list goes on and on, and the research supports that physical inactivity contributes to an increased risk in all of them. Our innate drive to move is overridden when we are sedentary and our bodies simply shut down and breakdown as a result.

Now we have all seen what ‘poor’ sitting posture looks like. The most common postural adaptations are:

– Rounding of the shoulders resulting in the chest and rib cage collapsing.

– Protruding neck or ‘chin poke’ contributing to weak and lengthened deep neck flexors/erector spinae/mid traps/ rhomboids.

– Weakening and shortening of pecs and levator scapulae.

– Flexed hips causing the hip flexors to shorten pulling the pelvis forward, whilst the glutes, hamstrings, and abdominals stretch and weaken.

It can be quite overwhelming to understand the flow-on effects of these adaptations but to keep it simple, all of these compensations limit our ability to take a full breath in and contribute to a stressed breathing pattern.

So how are we designed to breathe?

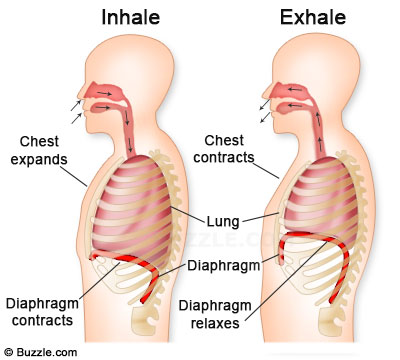

To inhale, the abdominal muscles should relax for the diaphragm to contract downwards and push our organs out of the way. The intercostal muscles should then contract to expand the rib cage and decrease pressure in the lungs to create a vacuum, drawing air into the lungs. To exhale, the diaphragm and intercostals need to relax to allow the abdominals to contract and push air out of the lungs.

Now imagine trying to blow a balloon up in a soup can compared to a large milo tin. The balloon’s ability to expand is limited by the size of the container you place it in. Your lungs work in the same way. If we sit in a slouched posture with our abdomen compressed, there is no room for our organs to move out of the way, limiting the ability of the diaphragm and intercostals to expand the lungs (i.e the container is smaller). This reduced expansion means a significantly reduced lung capacity (taking in less O2). Up to a 30% reduction in lung capacity has been observed in studies, which puts more stress on the heart and lungs, increasing the risk of an overall stress response in our bodies and our cortisol levels skyrocket. Elevated cortisol levels are linked with a wide range of medical conditions such as anxiety, weight gain, slowed healing, high blood pressure, fatigue, and headaches.

Movement is an acquired skill and if you’ve ever attended a yoga or Pilates class, you were likely constantly reminded to breathe by the instructor. At times you probably caught yourself holding your breath to help stabilise yourself in positions because the muscles meant to stabilise have lost their ability to. If you’ve lost a skill it will take time, like anything, to relearn and redevelop the correct technique. Practice doesn’t make perfect, it makes permanent. If we continue to down the path of inactivity, we are training ourselves to be less efficient and therefore placing more stress on our bodies in an already stressful environment.

Breathing Exercise

Keep it simple and start with the breath. Place one hand on the abdomen and one on your chest. Take a slow breath in, allowing the abdomen to press up into your bottom hand while the top hand stays relatively still. Breath out smoothly and feel the abdominals drawing the ribs down while imagining you are trying to make a candlelight flicker but not go out. Try first lying down and gradually progress to supported sitting, unsupported sitting, and standing. Add in more challenging functional movement patterns as your breath improves.

“If you can’t breathe in a position, you don’t own that position,” –Gray Cook

At Kinematics, we use various manual releasing techniques and exercises to improve not only posture but the efficiency of breathing mechanics to reduce stress on the body and improve overall function. We educate and empower our clients to self-manage and get moving again the way we were designed to move. Additionally, we offer Clinical Pilates 1:1’s and classes where we integrate breathing techniques to help increase lung capacity and facilitate correct movement. Poor movement patterns don’t always mean that you will present with pain, but there is always a more efficient way to move and we are here to ensure you do so!

By Amy Wiley

Physiotherapist + Pilates Instructor | Kinematics Health + Performance

Want to know more about the services we provide at Kinematics? You can learn more about our treatments here.