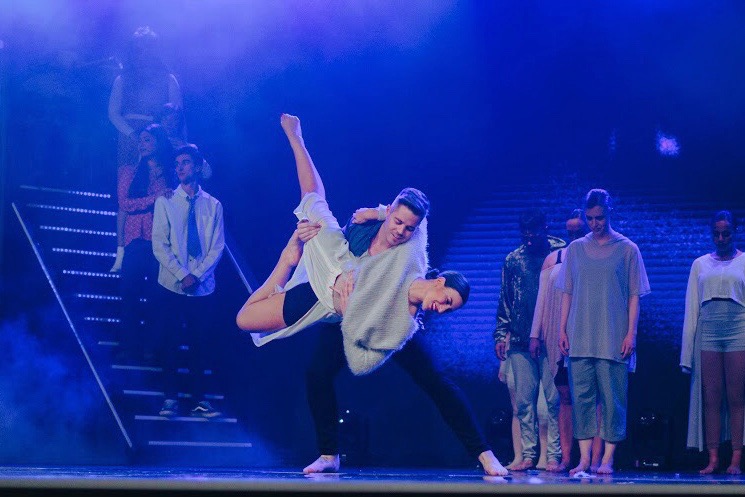

A dancers warm up.

May 16thAt the age of 12, I began dancing in shows alongside professional ballerinas from the Royal New Zealand Ballet. I remember seeing how intensely they warmed up and used to think they were mad doing all that extra work on their bodies right before a tiring 8-hour rehearsal. My warm up at that age consisted of sitting myself into a couple of painful stretches (making sure I could at least do the splits) then get my shoes on and be good to go. Certainly not ideal, but when you are young, uninjured and uneducated you don’t really understand the importance of adequately preparing your body to dance.

With any high-performance sport or activity, your body has to work hard to adapt to higher levels of stress, therefore it’s common sense that adequate preparation is needed for the increased energy demands… RIGHT?

To be completely honest my personal improvement in this area has been rather slow. In short, my journey went from doing practically nothing before my dance classes to entering into my teens showing up one hour before class started and absolutely OVER doing it with all kinds of static stretches my ballet teacher recommended I do. Little did I know at the time that by doing these stretches so regularly I was forcing my body to be extremely hypermobile and flexible but lacked any real core strength and stability, which would later catch up on me and my now injured body.

It’s only been during the last few years since entering into my 20’s that with all the vigorous training and high performance I still put my body through, I’ve noticed a huge increase in aches and pains! Warming up (and cooling down) correctly is now essential to me in preventing injury and fatigue. I now acknowledge how severely under educated I was in this area growing up – as most young dancers often are.

Why is a warm-up so important?

A proper (dance) warm-up should incorporate a number of dynamic movements to prepare the body for the strength, agility and the neuromuscular coordination required, and is ultimately aimed at reducing injury risk and facilitating optimal performance.

Firstly, a warm-up should ensure that the cardiovascular system and breathing rate gradually increase to soon meet the higher demand for energy when you begin dancing (or your chosen sport). Your body needs to consume more oxygen and fuel (glucose) to generate energy to power your muscles, and we know that oxygen reaches your muscles more efficiently when you engage your cardiovascular system. A byproduct of all this extra energy production is the increase in body temperature (giving a “warm-up” its name), so the cardiovascular component of a warm-up is vital in ensuring your body is ready to go.

Another important consideration during a warm-up is ensuring adequate sport-specific mobility is attained. Dancers put their bodies through all kinds of excessive ranges, in all directions, with all kinds of different impacts so therefore to reduce the risk of injury, muscle and joint mobilisation is necessary for effective warm-up. Dynamic movements increase the flow of synovial fluid (the lubricant in the joints) as well as the elasticity of muscles, facilitating increased range of movement. This also improves nerve signaling speed, therefore improving your overall balance, coordination and proprioception (your body’s ability to understand its orientation).

Photographer – Tammy Baird

Common Compensations

Throughout a dancers career, we are often repeatedly told (yelled at) to “suck in/brace/tighten” the abdominal region to ensure a flat “strong” stomach and to look thinner. From preschoolers to insecure teenagers going through puberty (the age bracket where behaviours and beliefs are embedded into who we are at a subconscious state), most of us have been poorly educated as to how to attain real core strength.

It wasn’t until I embarked on my Pilates instructor studies through Tensegrity Training that I really learned how to correctly engage my core and produce more efficient movement within my body. I’m almost embarrassed to say that for most of my life I have thought my core was strong seeing as I had that desired flat 6 pack stomach… In reality, I was just blessed with some good genetics (thanks Mum) and that by “pulling up” and “bracing” like every dance teacher I’ve ever had has told me to do, instead it was my psoas and hip flexors that were in overdrive 90% of the time, not my core. This has a crucial domino effect on the mechanics of breathing and movement patterns involving the spine, pelvis, glutes, hamstrings the list continues as we know the body is a connected unit.

Tightening of the iliopsoas muscle can pull the shoulders and thoracic spine into flexion. To maintain this posture, erector spinae muscles in the lower back tighten causing an anterior shift of the pelvis – more commonly known as a “swayed back.” Over time, the hip flexors become short and tight and the hamstrings long and weak which is a recipe for disaster for any dancer who is continuously overstretching their hamstrings to be able to do the splits and doing 100 crunches a day to get them abs!

It is therefore important to incorporate spinal mobility exercises into a dancers warm-up to encourage correct pelvic alignment and efficient use of inner core muscles.

The desired requirement of dancers to have an unrealistic 180 degrees of turnout creates many other biomechanical compensations. Forcing the feet to achieve a turnout position beyond what the hips will allow is probably the most serious training error a dancer can make. Turnout refers to the outward rotation of the legs and feet, the knees are straight and the legs are externally rotated ideally from the hips. These compensations may be allowed and even encouraged by dance teachers who stress the importance of ideal flat turnout which, unfortunately, leads to many of the musculoskeletal injuries seen in a dancers’ ankles knees and hips.

Rolling in off the feet is a common compensatory technique used to increase this unachievable goal of a flat turnout. This manoeuvre involves forced pronation, placing excessive load on the extrinsic muscles in a futile effort to stabilize the longitudinal arch of the foot. This may predispose the tendons and their associated attachments to overuse injuries such as posteromedial shin splints, flexor hallucis longus tenosynovitis, or plantar fasciitis. The inclusion of foot and ankle mobility exercises as part of the warm-up can help to encourage correct load transfer, reducing injury risk.

Another area that gets placed under excessive pressure in order to gain the desired turnout range is the knee. The dancer assumes a demi plie position (half-squat in the first position) and places the feet in 180 degrees of turnout, then forcefully straightens the knees without moving the feet, “screwing the knee”. In normal biomechanics, the femur internally rotates on the tibia during end-range knee extension. ‘‘Screwing the knee’’ places shear forces on the knee because the femur needs to internally rotate with full extension while the tibia and foot are passively held in external rotation due to the 180° of turnout. This force may place extraordinary stress on the medial aspect of the knee, commonly causing injury to the medial collateral ligament and the medial meniscus.

Those with less than ideal turnout can also force more by increasing their lumbar lordosis – another cause to anteriorly tilting the pelvis which creates space for the hips to be able to rotate. A hyperlordotic posture predisposes a dancer to lower back pain which is another common area of concern.

In order to prevent these common compensations and injuries, it is important to not only be more realistic about turn-out expectations for those of us not born/able to achieve 180-degree range, but ensure full hip external rotation range is achieved as part of the warm-up .

The following is an exemplary warm up I use to prepare my body for dance rehearsals and performances…

Step 1 of a dance warm-up:

– Simple rhythmical movements for about 10 minutes

– This raises internal body temperature 1 – 2 degrees

– Increase heart rate and the blood flow to the muscles

Step 2 of a dance warm-up:

– Mobilisations of the joints

– Gradually increase the range of motion

– Increase the synovial fluid in the joints

Step 3 of a dance warm-up:

Dynamic stretching out hips, feet and legs, in particular:

– Calves, hamstrings, quadriceps and glutes

– TFL and hip flexors (usually tight due to postural patterns discussed above)

– Piriformis muscle (assists with rotating your hips and turning out your feet)

Step 4 of a dance warm-up

More complex movements increasing speed and power including jumping and rehearsal choreography (reproducing the movement patterns required for the dancing you are about to undertake).

It is important to note that only dynamic stretching should be used in your warm up, taking your body carefully through full ranges of motion. Static stretching actually reduces strength and stability, and therefore should be saved for your cool-down.

Check out the video shown on our Instagram page for one short example of a series of exercises I do to incorporate steps 2 + 3.

NB: You will need: a (broom)stick and a foam roller

This demonstration includes:

- Foot mobility

- Spine articulation

- Calf + ankle mobility

- Hamstring stretches + thoracic rotations

- Hip + lumbar spine mobility

- Thoracic extensions + core activation

- Lumbar flexion + extension, shoulder stability, scapular retraction and protraction

- Lunges targeting glutes stretching psoas + front of hips with added thoracic rotations + hip external rotations

- Side lunges to target adductors

- Lateral flexion mobility

As well as increasing heart rate, mobilising joints and elongating some key muscles, this warm-up sequence tests balance, control and coordination – which is vital for any athlete, particularly dancers.

By Raffaella Cheruseo