Sore Hips After Running?

November 24thHip pain is a common issue suffered by many athletes, especially runners. This is largely due to the hip joint playing such a crucial role in flexibility, stability and power during running.

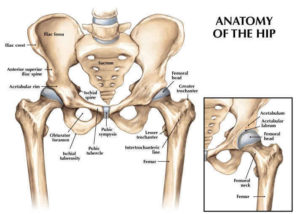

The hip is the body’s second largest weight-bearing joint (after the knee) and functions as a ball and socket joint. The “ball-like” head of the femur bone articulates with the “socket-like” surface of the acetabulum to allow for both mobility and stability of the hip.

Both bony surfaces are coated with a protective articular cartilage. The socket also has a rim of rubbery fibrocartilage called the labrum. The labrum helps to deepen the socket and further increase joint stability.

The entire joint is covered with a capsule containing joint fluid to maintain cartilage lubrication.

Various muscles attach around the hip to allow for the required movements of the joint. These muscles are often divided into four groups according to their orientation around the hip joint: the gluteal group; the lateral rotator group; the adductor group; and the iliopsoas group.

Hip pain from running occurs when there are damage, disorders, inflammation, or injuries to any of the tissues or bones that comprise the hip joint (or to a neighbouring source causing referred hip pain). However, often the main reason these structures break down in the first place is from poor pelvic and hip alignment causing excessive load on the hip region.

Pelvic and Hip Alignment

The pelvis provides the bony link between the spinal column and the lower limbs, acting as an intermediary in the load transfer mechanism from the trunk to the legs and vice versa. Alignment issues of the pelvis lead to increased strain and force on one hip compared to the other. This can lead to a functional leg length discrepancy, and even further secondary movement compensations. Therefore, maintaining optimal pelvic alignment is crucial to ensure efficient running biomechanics and to avoid injury.

There are numerous potential contributors to poor pelvic alignment including:

1. Immobility

Thanks to the convenience of technology and our modern lifestyles, people are more inactive than ever. Even if you’re doing 30 minutes per day of physical activity, it matters what you do the other 23 hours of the day. Sitting and being in flexed positions for long periods of time causes the shortening of certain muscle groups such as the iliopsoas (hip flexor). Hip flexor tightness results in a reduction in hip extension range. Adequate hip extension is crucial for efficient running biomechanics and without it, the body will compensate in another area in order to propel the body forwards e.g pelvic rotation which places more load through the hip joint -> hip pain and/or injury.

The other main immobility issue we see in our runners (and most population groups) is a reduction in thoracic spine extension and rotation. Similar to the hip flexors, thoracic spine immobilty can effect pelvic alignment and cause compensatory movement patterns. E.g. A more flexed thoracic spine in a runner generally results in an increase in horizontal arm swing which results in not only an inefficient gait but also creates more load distribution to the lower limbs (including the hip joint!) -> pain and/or injury!

2. Strength deficits and instability

Prolonged sitting postures also disrupt the firing of certain muscle groups, the most common being the glutes. There are 3 main glute muscles whose primary roles are stabilisation and extension of the hip. Therefore an activation or strength deficit within any one of the glute muscles has a huge impact on pelvic alignment and controlling the forces through the hip during gait.

Another key hip and pelvic stabiliser that tends to be weak are the adductor (“groin”) muscles. The hip adductors are made up of five muscles whose primary role is to bring the hip back toward the midline, making them vital to pelvic stability. As you run, the contraction of the adductors aid in the forward and backward motion of your swing leg during your running stride. These muscles are also constantly working to stabilise the equilibrium of the trunk by a constant adjustment of the pelvis. Therfore inadequate adductor strength commonly results in poor pelvic alignment and inefficient running biomechanics.

Other common contributing factors to poor running biomechanics and hip pain:

Treadmill Running

On a treadmill, the backward motion of the belt assists the runner by pulling the feet back. This results in less work for the hip extensors (glutes and hamstrings) and therefore does not directly translate to ideal outdoor running mechanics. The machines are also not usually capable of simulating downhill running, which is an essential part of any training program. Depending on your running training and goals, treadmill running may still be beneficial for you however it’s important to consider the possible biomechanical impact.

Footwear

There are many different types of footwear available on the market for runners. Many of these shoes claim to improve a runner’s efficiency by altering their stride mechanics. E.g. Minimalist footwear claims to aid runners in running more on their forefeet whereas more traditional footwear provides more cushioning specifically for a heel-first landing. Wearing inadequate footwear for you and your running style increases injury risk significantly. The most common issue we see is clients wearing far too supportive footwear. Too much arch support blocks the required foot pronation to efficiently push off through the big toe and propel the body forwards. This leads to an increased lateral loading of the lower limbs and often presents in lateral hip pain.

To find your ideal running footwear, we recommend the team at The Running Company, Cliffton Hill.

Sudden change in load

Many people set out with great intentions on their running but increase their training load too quickly and end up getting injured. Load essentially means how ‘hard’ your body is working, and there are many things influence it – such as how far you run (distance), how fast you run (speed), how often you run (frequency), even where you run (surface – eg flat vs. hilly). It’s important to recognise that changing any one of these components can change the overall load on your body.

The key message is to start small, gradually build up and only increase one of these factors at a time, rather than all at once. Your body will adapt, provided you give it time to.

Previous Injuries

Another common root cause of running related (and other overuse) injury we see is poor rehabilitation from a previous injury. For example, even with a simple ankle sprain, neurological pathways which provide essential feedback to the brain as to what is happening with the foot are disrupted. Not only is the injured ankle then predisposed to another injury, the body will also naturally compensate to offload weight onto the other leg to try and allow the ankle tissues to heal. This can then result in a secondary (sometimes more serious) injury on the overloaded side. Without addressing the original ankle This is another reason our clinicians don’t just look at the site of pain or injury when carrying out a biomechanical assessment as often the dysfunctional movement pattern causing the pain is elsewhere in the body!

Although we have discussed a few contributing factors that lead to inefficient running biomechanics and hip pain, there are many others not mentioned in this blog. At Kinematics we always endeavour to provide a thorough and long term solution by addressing full-body alignment and movement dysfunctions, rather than just symptomatic relief.

Our top 5 tips for preventing hip and other running related injuries:

-

Have your running biomechanics assessed

-

Have your footwear assessed (we recommend running company)

-

Maintain as active as possible when not running (e.g. reduce time spent in a flexed position)

-

Incorporate mobility to address muscle length imbalances

-

Incorporate strength work to address strength and stability imbalances

Book an appointment here.

By the Kinematics Team